Examination of the Israeli perspective shows that some of the territories on the Golan Heights, which have been under Israeli control since the Six-Day War, should have already been included within the boundaries of the Jewish national homeland that was supposed to be established upon the end of the British Mandate over the Land of Israel.

The control over the Golan Heights has been under dispute for one hundred years. In 1916, upon the defeat of the Ottoman Empire during World War I, after about 400 years of control over the region, the United Kingdom and France signed the Sykes-Picot Agreement. The agreement divided the occupied territories of the Ottoman Empire into areas of British and French control. The agreement prescribed that the area of the Land of Israel, including the territories east of the Jordan River (today, the Kingdom of Jordan) and Iraq would be transferred to British control, while the area known today as Syria would be transferred to French control.

The British and the French are entering the Middle East

In 1919, after World War I, the League of Nations founded the mandate regime – a regime that would apply to territories that the Ottoman Empire had controlled prior to the war but were no longer under Ottoman sovereignty, and to the peoples living in those territories who were not yet considered “able to stand on their own.” The agreement prescribed that the control over these territories would be divided and entrusted to the victorious allied powers until it became feasible to hand them over for self-governance by the peoples living in them.

In 1920, a conference convened in the city of San Remo, Italy, which was attended by the United Kingdom, France, Italy, Japan and the United States (as a neutral observer) with the aforesaid objective of partitioning the territories of the Ottoman Empire between the world powers that were victorious during the World War. The conference decided that the territories that Britain and France had seized from the Ottoman Empire would not be annexed to them, but rather entrusted to them as stated until new countries are established. Furthermore, the San Remo Conference adopted the Balfour Declaration that the British government had issued in 1917, which stated that, upon the end of the British Mandate over the Land of Israel, its territories will be set aside for the establishment of a homeland for the Jewish people.

The resolution passed by the San Remo Conference concerning the Land of Israel, de facto, consolidated the Balfour Declaration with the mandate regime and, in essence, it constituted the basic document that established the British Mandate and provided the foundation under which it was mandated to act. The British Mandate is a legal instrument, the validity of which is tantamount to a binding international treaty, and it was also ratified by the League of Nations, which also adopted the principles appearing in the Balfour Declaration.

The Arab Kingdom of Syria, ruled by King Faisal I, was formed at the beginning of 1920 in the region known to us today as Syria. This was an initial short-lived attempt to establish independence in the region after the fall of the Ottoman Empire. The formation of the new Syrian entity did not coincide with the accords to implement the mandate regime after World War I, which led to clashes between the French and the new Syrian entity. The revolt was quashed in July 1920 during the Battle of Maysalun that was waged between the forces of the Arab Kingdom of Syria and the French, and ended with the French victory and the toppling of the short-lived Syrian Kingdom. After the French took over the territory, they identified the ethnic and tribal divisiveness in the region as a factor that was frustrating any possibility of establishing a single state operating under a central government. To a certain extent, the French understood already back then, what today – about one hundred years later – is quite obvious: a single Syrian State does not reflect the reality in the field.

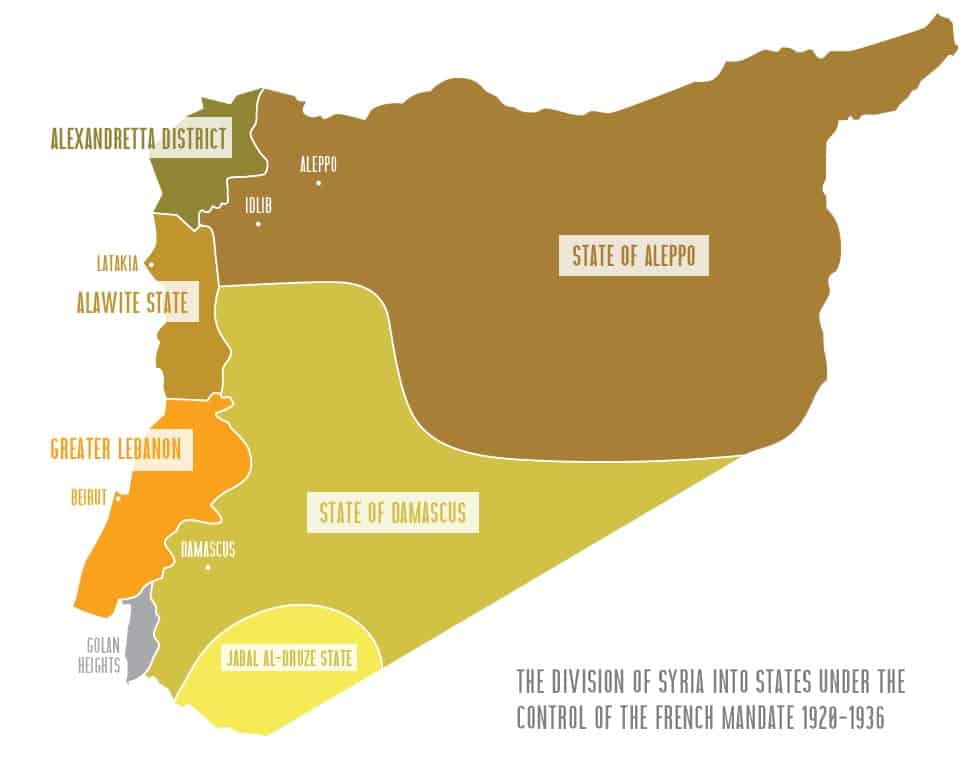

The French applied the ‘divide and conquer’ approach and divided the territory of the Syrian Kingdom into six regions of control comprised of six political entities: Lebanon, Damascus, Aleppo, the Alawite State, the Sanjak of Alexandretta and Jabal al-Druze. Each of these political entities received autonomous authorities, thereby severing the artificial consolidation of the regions of the Syrian Kingdom. This course of action was welcomed by the minority populations, whose status improved as a result of the cooperation with the French, particularly by the Maronites in Lebanon, who were considered to be under the patronage of the French, culturally, economically and politically.

Demarcation of the border – and its change

The San Remo Conference, which, as stated, convened in 1920, did not define the borders between the regions of control of the United Kingdom and France; it was decided that the borders would be determined in a separate treaty between the British and the French. The starting point that the parties defined for the discussion of the question of the borders of the Land of Israel was the biblical borders of the land as described in the Bible, which extended from “Dan to Be’er Sheva” (in biblical times, Dan was a city in the Golan). This starting point shows that the French and the British attributed importance to the historic-cultural context of the land, and considered its past – the historic homeland of the Jewish people – as a political reference point that is relevant to its future. The borderline between the British Mandate and the French Mandate was supposed to pass through the territory that is today identified as the region of southern Lebanon, the Upper Galilee and the Golan Heights.

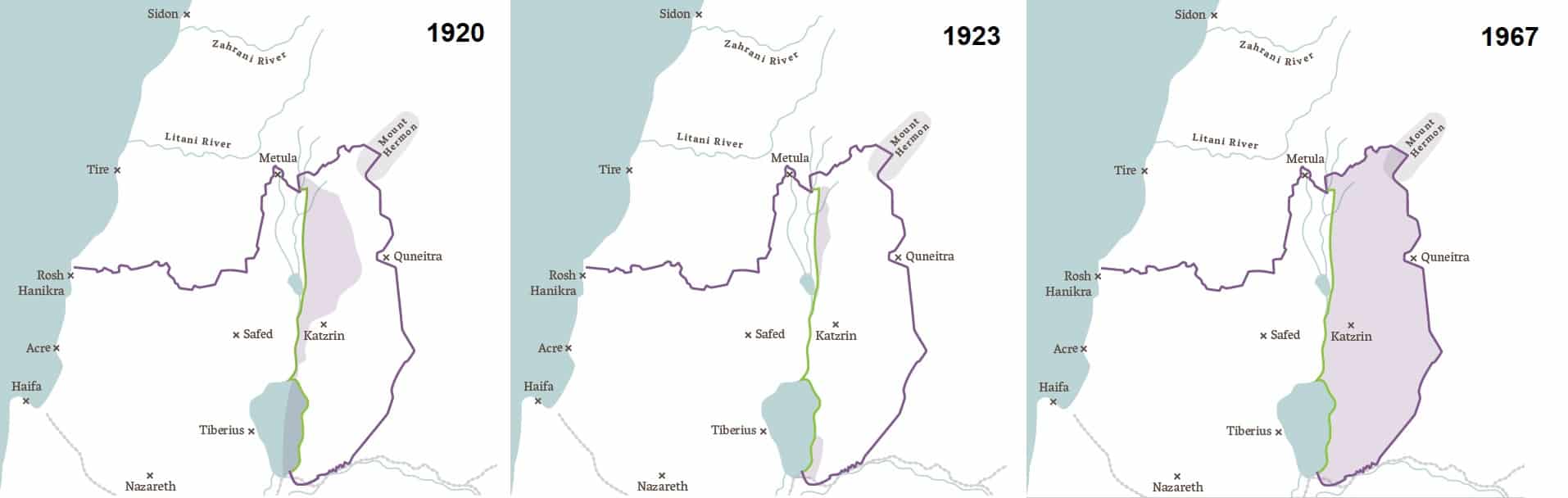

The British attributed considerable importance to the sources of water in the region. In 1919, during internal discussions of the demarcation of the borders of the Land of Israel, the British defined the desirable northern borderline of the Land of Israel at the Litani River in the north and continuing eastward and including the Golan and the Hauran. In the final analysis, political considerations prevailed over these principles. According to the regions of control defined in the agreement signed in November 1919 between the British and the French, the communities of Metula, Hamara, Tel-Hai and Kfar Giladi suddenly became defenseless Jewish enclaves exposed to Arab invasions within the territory of the French Mandate. One of the grave repercussions of this course of action was the Battle of Tel-Hai, which resulted in these communities being abandoned for several months.

In 1920, the parties agreed that the borderline between the two mandate regions would pass through the center of the Sea of Galilee, ascend northward and would leave significant parts, but not all, of the Golan within the boundaries of the British Mandate. These accords were signed, thereby recognizing the borderline between the British Mandate and the French Mandate for the first time; however, in 1923, the French had second thoughts about the agreements that were reached three years earlier and asked to re-demarcate the borderline. The British acceded to the request and a joint delegation was sent to the Golan Heights region, headed by Lieutenant-Colonel Paulet from France and Lieutenant-Colonel Newcombe from England, who were appointed to lead the joint boundary commission. After holding discussions about the control over the sources of water, and after additional French demands, an amended borderline was agreed upon that changed the borderline agreed upon in 1920. The Franco-British northern border agreement of 1923, which was also called the Paulet-Newcombe Agreement, prescribed that the British will transfer to the French Mandate the majority of the territories from the region of the Golan that had been within the bounds of the British Mandate according to the original agreement. Within this scope, the borders of the Land of Israel were shifted to exclude the Banias River and the Hasbani River (one of the three sources of the Jordan River) with the argument that they are vital to the subsistence of the Arab villages in the region.

As stated, the most significant change in the demarcation of the border in the Golan was made in the territory between the Banias River and the Sea of Galilee. During the demarcation of the borderline, the British and French delegations encountered situations whereby the borders of private lands of Arabs living in the Golan were unclear. Since there were no maps that delineated the ownerships in the area, the heads of the delegations assembled the leaders of the villages on both sides of the agreed borderline, and asked them to arbitrarily indicate the borders of the private lands. When the parties reached an agreement, the delegation heads “shifted” the agreed borderline according to these delineations and set a new borderline.

The members of the Bani Fadil Bedouin tribe who lived in the region claimed that the territory between Quneitra and the Jordan River is privately owned land and that the new borderline crosses the tribal lands, resulting in part of the tribe being on the Syrian side of the border, and part on the Land of Israel side. Notwithstanding the obligation to consider long-range considerations by virtue of the mandates issued to them, the British and the French decided to attribute decisive weight to this consideration when setting the borderline. They allowed the tribe’s chief to decide whether his tribe would be under British sovereignty in the Land of Israel – and in that case, the borderline would be shifted eastward to Quneitra, or whether it wanted to be under the French-Syrian sovereignty – and then the borderline would be shifted to the Jordan River. The tribe’s chief opted to remain under French sovereignty and the borderline was moved west. This was an arbitrary decision that created an historic fact and led to the shifting of the border of the future Land of Israel westward. The territory of the Golan Heights was removed from the bounds of the British Mandate and, in effect, from the bounds of the northern border of the future State of Israel.

The assertion that the 1923 borders are the official borders between Israel and Syria is under dispute. The main claim is that the territory exchanges by the British and French were done contrary to the gist of the decisions reached by the 1920 San Remo Conference and that, de facto – due to internal considerations that served a temporary situation – the British had transferred territories in the Golan to the French, in violation of the terms of the mandate granted to them, territories that had been designated for the establishment of the Jewish homeland and were part of the British Mandate during its first three years. Later, the new borderline delineated by the British and French Mandates in 1923 was recognized as the demarcation of the international border.

World War II created further uncertainty with regard to the border arrangement defined at the end of World War I. Upon the end of the war in 1945, the San Francisco Conference on International Organization was convened by the United Nations (which replaced the League of Nations) and reaffirmed the validity of the rights that were granted to nations within the scope of the League of Nations’ mandates. The San Francisco Conference also ratified the validity of the legal instrument of the British Mandate over the Land of Israel and the mandate deed remained a binding international agreement between the countries.

The Syrian aggression

In 1946, the French Mandate in Syria officially ended, and an independent Syrian country was established at the international borders of the territory of the French Mandate, including the territories in the Golan and in the Hauran which, as stated, the British had handed over to the French in 1923. De facto, the 1923 borderline had become the international borderline as of the end of the French Mandate in 1946 and until the War of Independence in 1948. During the War of Independence, Syria took an active part in the all-out Arab attack on the State of Israel and conquered additional territories in the region of the border east of the Sea of Galilee, as well as the region at the head of the Banias River and mainly in the region of Mishmar HaYarden. The finish lines of the war deviated from the 1923 borderlines which, as stated, had constituted, from 1946 (Syria’s independence) until May 1948, the official southern border of the independent Syria. Syria used the territories that it had invaded as launch points for constant shelling of communities in northern Israel. From the end of the War of Independence and until 1967, Syrian forces were deployed in some of the demilitarized regions west of the international border, including the region of al-Hamma and the northeastern bank of the Sea of Galilee, in violation of the disarmament agreement signed in 1949 after the War of Independence.

Towards the end of 1966, the situation in the region was exacerbated as a result of political changes in Syria and in the region, including the Syrian-Egyptian Alliance and the intensifying involvement of the former Soviet Union. The border incidents in the demilitarized zones, coupled with Syrian armament with Soviet support and tactics to divert the sources of water flowing from Mount Hermon to Israel – all of these compelled Israel to reach a decision. In mid-1967, on the fifth day of the Six-Day War, Israel launched a defensive war in order to eliminate the constant threat to northern Israel originating from the mountains of the Golan and to create a buffer zone between it and the Syrian aggression.

It should be noted that Syria never accepted the borderline that was set in 1923. During all contacts held with the Syrians after the Six-Day War, Syria had demanded that the borderline should cross the Sea of Galilee and Lake Hula. During the negotiations between Israel and Syria between 1992 and 1996, the Syrians had demanded Israeli withdrawal to the banks of the Sea of Galilee, according to the route that was actually carved out between the parties between 1949 and 1967.

An historical analysis of the control over the Golan over the last one hundred years shows that the borderline between Israel and Syria is under dispute and is subject to interpretation. Examination of the Israeli perspective shows that some of the territories on the Golan Heights, which have been under Israeli control since the Six-Day War, should have already been included within the boundaries of the Jewish national homeland that was supposed to be established upon the end of the British Mandate over the Land of Israel.