Decentralization of the Syrian arena is an Israeli interest that would break up the Syrian united front against Israel in a way that will necessarily weaken the threat to Israel’s northern border both strategically and on a long-range basis.

In some sense, the civil war in Syria reverted the country to its natural situation before the world powers began intervening at the end of World War I. This is not a new situation, but rather a return to the starting point, to the natural state of the region before the Western powers forced political organization on it that is incompatible with the ethnic and religious characteristics of the peoples living in the region. This old-new reality offers Israel new opportunities.

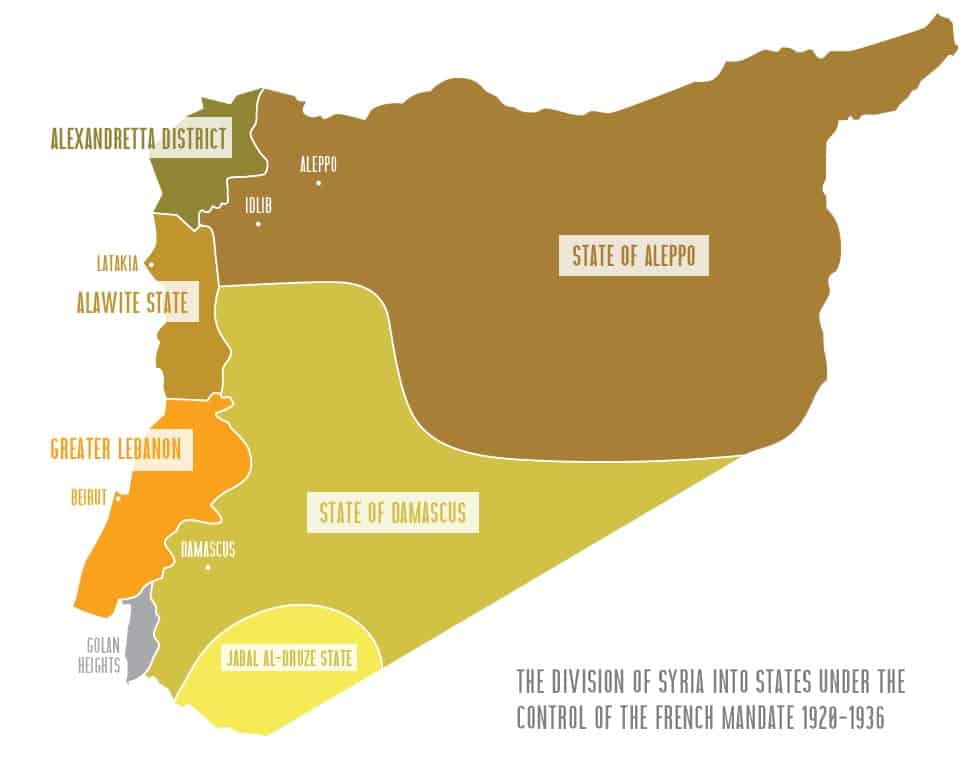

Since it was established in 1946, Syria has been a hodgepodge of peoples cohabiting a space built on a rickety equilibrium that somehow managed to survive for nearly 70 years, despite numerous crises. During the quarter-century that preceded Syria’s independence, the Syrian arena suffered many upheavals. At the end of World War I, upon the downfall of the Ottoman Empire, a short-lived kingdom was established in the region. Upon the French victory, governance of the region shifted to the model of the French Mandate and was called ‘French Syria.” Already at the outset, the French quickly became cognizant of the fact that the ethnic and religious groups living in Syria have no common national identity and that it will be extremely difficult to collectively govern them under a central government. This understanding of the complex reality in the Syrian arena led the French to the conclusion that autonomy should be granted to the six major groups living in the region under the French Mandate. At the beginning of the 1920s, the French allowed the delineation of six States in French Syria:

- The State of Aleppo and the State of Damascus: extensive Sunni regions in central Syria and in the desert region, which extend over nearly the entire northeastern border of Syria;

- The Alawite State: along the Mediterranean coast, in the vicinity of the port city of Latakia;

- The Jabal al-Druze State: in southern Syria, on the Jabal al-Druze mountain, which was also called the “State of Souaida”;

- Greater Lebanon: the Lebanon of today, which was the homeland of the Maronite Christians;

- Alexandretta District: in the Sanjak of Alexandretta (İskenderun) in northwestern Syria;

- A Kurdish region in Syria that the French refused to recognize as an independent state; nevertheless, the northeastern part of the Kurdish region was governed as a quasi-autonomous region.

In 1936, after about 15 years of these decentralized autonomies, the French decided to retake full control over French Syria, apart from two regions: Lebanon, which remained independent, and the Sanjak of Alexandretta, which was later transferred to Turkey. In 1938, the Turkish military entered the Sanjak of Alexandretta, launched a campaign of ethnic cleansing of all of its non-Turkish residents, changed its name and established a Turkish government. The Turkish government held a referendum, which found that the majority of the people wanted to remain under Turkish sovereignty. In this way, extensive territory was removed from Syrian sovereignty, territory that is about three times the size of the area of the Golan currently under Israeli control.

As stated, Syria’s reversion to a model of a single State under the French Mandate did not reflect the ethnic divisiveness in the region. The concern that the change would trigger bloodshed between the factions in Syria prompted a group of Alawite intellectuals – including Sulayman al-Assad, Bashar al-Assad’s grandfather – to send an urgent petition to French Prime Minister Léon Blum in June 1936, warning about the foreseeable ramifications of the forced consolidation, and expressing their concern about the termination of the French Mandate regime.

A fascinating sidebar is the reference in this petition to the suffering of the Jews by the founder of the Assad dynasty and by the other Alawite leaders. In this petition, they compared the plight of the Syrian minorities to that of the Jews, referring to the similar persecution suffered by the minorities in Syria (non-Sunnis) and the Jews living in the Land of Israel (one can assume that Assad and the other Alawite dignitaries were leveraging the fact that Prime Minister Blum was a Jew and in favor of the Zionist project):

“The spirit of fanaticism and narrow-mindedness, whose roots are deep in the heart of the Arab Muslims toward all those who are not Muslim, is the spirit that continually feeds the Islamic religion, and therefore there is no hope that the situation will change. If the Mandate is cancelled, the danger of death and destruction will be a threat upon the minorities in Syria, even if the cancellation [of the Mandate] will decree freedom of thought and freedom of religion.”

“Those good Jews, who have brought to the Muslim Arabs civilization and peace, and have spread wealth and prosperity to the land of Palestine, have not hurt anyone and have not taken anything by force, and nevertheless the Muslims have declared holy war against them and have not hesitated to slaughter their children and their women despite the fact that England is in Palestine and France is in Syria. Therefore, a black future awaits the Jews and the other minorities if the Mandate is cancelled and Muslim Syria is unified with Muslim Palestine. This union is the ultimate goal of the Muslim Arabs.”

The French Mandate over French Syria, which lasted about a quarter-century, was terminated at the end of World War II. In 1946, for the first time, Syria officially became an independent country (Lebanon received its independence in 1943). The international recognition of Syria as a country did not change the fact that Syria always was and firmly remains a hodgepodge of peoples and ethnic groups that are hostile towards each other.

Syria’s development as an independent country has been fraught with difficulties and has suffered numerous upheavals. One of the most significant events was the coup d’état in 1970, which cemented the Alawites’ take-over of the country based on their command of the military and control over the Ba’ath Party. The minority Alawite regime headed by the Assad family guaranteed its firm grip on the government through the use of brutality and oppression, a policy of divide-and-conquer of the ethnic groups in general, and by creating a minority coalition that controlled the Sunni majority in particular. One manifestation of the oppressive Alawite regime in Syria occurred in 1982, when Hafez al-Assad ordered the Syrian military to crush an attempted Sunni uprising against his regime, which resulted in the massacre of tens of thousands of people in the city of Hama.

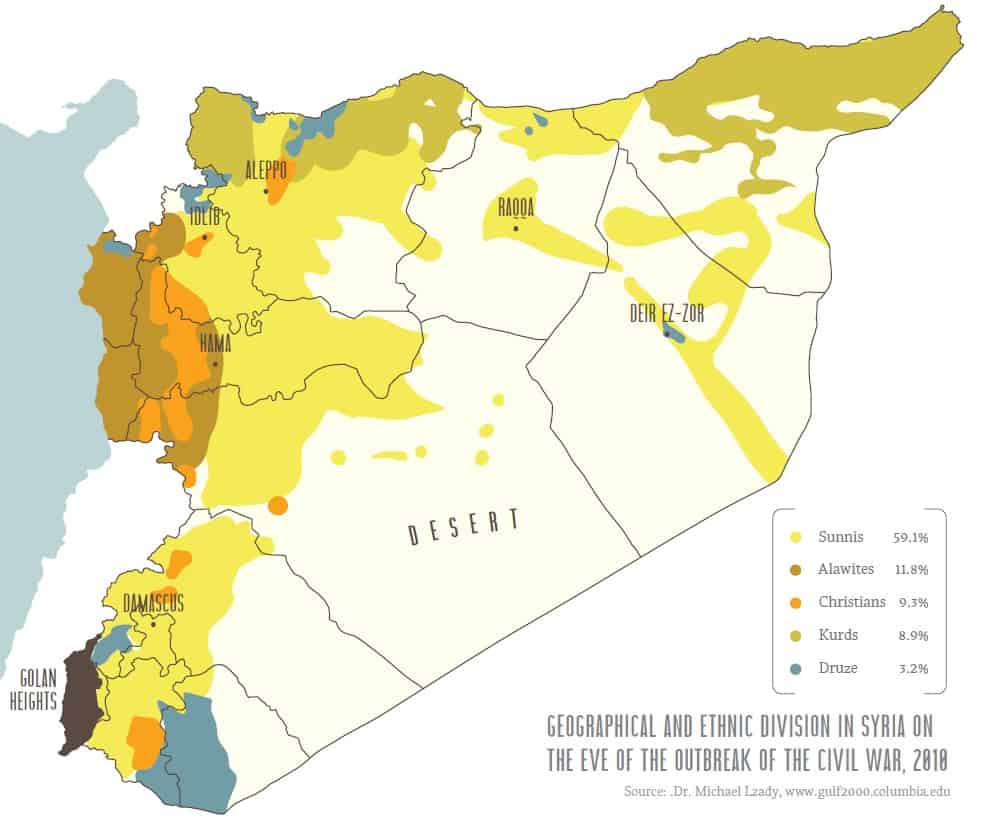

The Syrian melting pot failed and reached the melt-down point in 2010. The regional and domestic arrangements in Syria that had been in place for about one hundred years began collapsing one after the other and degenerated to the point of bloody tribal and ethnic wars. At the outbreak of the civil war, about 60% of the population of Syria was Sunni. The remaining 40% were ethnic minorities: only about 12% of the population were members of the ruling Alawite community; about 9% were Christians, 3% were Druze and about 9% were Kurds.

For years, the social structure in Syria was predicated on maintaining the tenuous equilibrium among the population segments in the country. It was clear to all of the parties that any upset of this delicate balance could potentially trigger a bloody civil war. The fulcrum was the Alawite government, the overlord of a “coalition of outcasts,” comprised of subjugated Syrian minority political groups. This fragile equilibrium was sustained by forcing all minorities in Syria to participate in the political game, by dividing the resources – and by the regime’s policy of crushing any rebellion that arose from time to time through extreme brutality.

However, the Syrian conglomeration was not only based on the equation of the “coalition of outcasts.” The Syrian regime employed another key strategy in order to avoid domestic conflicts and divert attention from internal strife: the Syrian regime conjured national unity using a base common denominator – the fabrication of a common enemy (“the Zionist enemy”) and vehement opposition to the existence of the State of Israel. Throughout the years of Syria’s existence, the Syrian military has been completely obsessed with attacking Israel – thereby forcing Israel to contend with major threats over many decades. Syria’s aggression included attacks on Israeli communities, deployments of terrorist cells, strategic threats posed by an arsenal of chemical weapons and, above all – its actual attempts to destroy Israel, the primary example being the Yom Kippur War in 1973.

From the forward-looking security-strategic perspective (but disregarding the erosion of the Syrian military’s absolute power during the civil war), Israel has an interest in decentralizing and splitting up any potential of a hostile military force on its eastern front of tomorrow. The balance of powers will fundamentally change in a way that is favorable for Israel, when and if the Syrian-Iraqi arena is split up into several political entities. In this scenario, Israel will not be forced to defend itself against a single united immense military force that devotes all of its resources to attacking Israel, but rather, against disjointed smaller forces. On the other hand, a concentration of pro-Iranian Shi’ite forces, comprised of Iranian units, Shi’ite militias, the Hezbollah and Alawite forces in Syria – is a scenario that creates a new and complex security threat to Israel.

The establishment of new-old independent entities, which would reflect the religious-ethnic reality in the Syrian arena, could create a new balance of powers, and would also necessarily change the geo-strategic balance on Israel’s northern border. It is possible that some of these new entities will see themselves as partners in a new alliance of minorities in the region, together with Israel – while the rest will be preoccupied contending with numerous ethnic/tribal/religious conflicts in a multi-front arena, such that their aggressive intentions will not be directed solely against Israel. Decentralization of the Syrian arena is an Israeli interest that would break up the Syrian united front against Israel in a way that will necessarily weaken the threat to Israel’s northern border both strategically and on a long-range basis.