For the first time in fifty years, there is an opportunity to change borders in the Middle East, and an opportunity for Israel to receive recognition of its sovereignty over the Golan as a byproduct of the civil war in Syria.

Israel has a clear interest in maintaining its sovereignty over the Golan and in receiving international recognition of its sovereignty.

The expiration of the arrangements that defined the borders and the States in the Middle East after World War I poses a major challenge for Israel, and requires it to revise its geo-strategic interests prospectively and not retrospectively. It must take all possible action in order to ensure that its needs are discussed during the debates among the world powers about the future of Syria and the Assad regime. For the first time in fifty years, there is an opportunity to change borders in the Middle East, and an opportunity for Israel to receive recognition of its sovereignty over the Golan as a byproduct of the civil war in Syria.

Earthquake in the Middle East

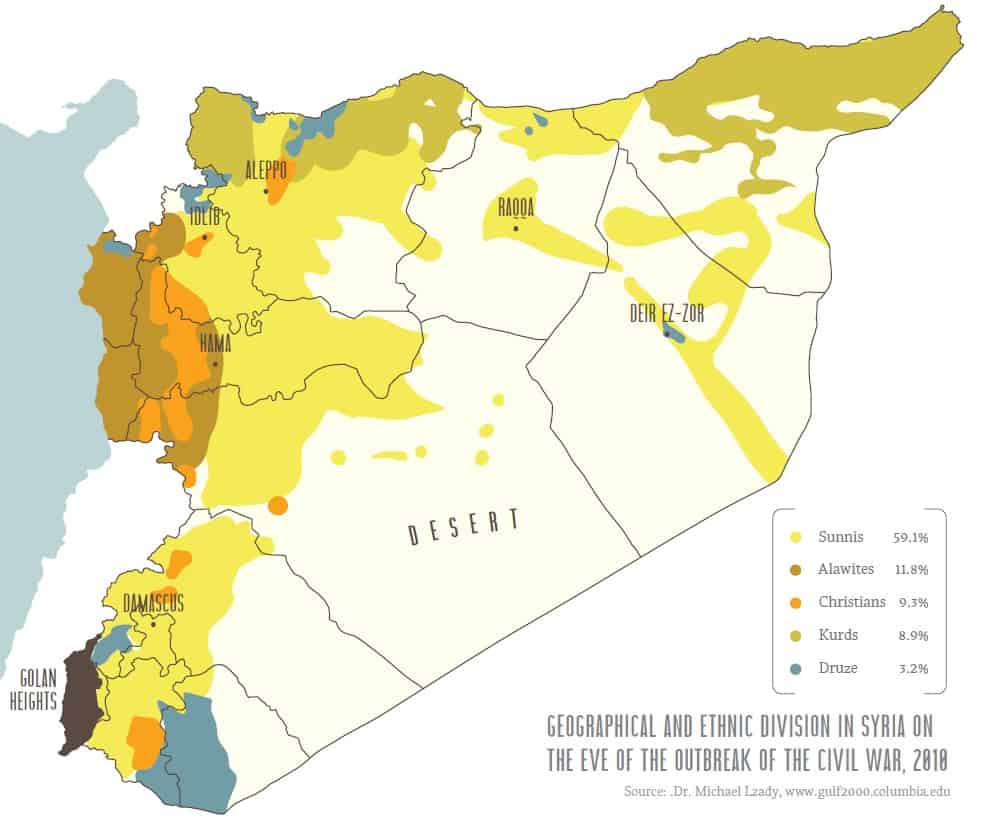

The Arab Spring and the civil war in Syria that erupted in its aftermath towards the end of 2010 created a new regional reality in the Middle East. This new reality undermined the regional order that was in play over the last hundred years, since the Sikes-Picot agreements, and placed in question some of the borders in the region. A look at what is happening in countries like Iraq, Syria and Libya attests to the fact that the reality that the world has acquiesced to up until now is gone and will never return. New-old power groups based on religious and tribal foundations are undermining the existing regimes and are dividing regions of influence amongst themselves that are blurring the recognized borders. Wide-scale forced movements of populations and the de facto formation of autonomous regions that are defined on the basis of an ethnic or religious identity, are reshaping the living space of the human mosaic that comprises the region. A report released recently by the British House of Commons about trends in the Middle East found that the concept of a “state” is steadily losing relevance in particular regions in the Middle East, and it appears that the subterranean shifts that have been occurring over decades are suddenly bursting from the depths of the earth and are creating a new social and human topography.

In the arena closest to Israel, Syria is attracting most of the attention. It appears that Syria will no longer exist as a single State as we once knew. Even if Assad succeeds in imposing his rule on the residents still remaining in Syria in the aftermath of the civil war, it will be an artificial regime whose authority relies on foreign forces. The prospects of subjugating diverse ethnic groups under an artificial government are not good.

When the civil war broke out in Syria, Israel officially remained neutral. Initially, the Israeli security establishment, headed by the former Minister of Defense Ehud Barak, assessed that Assad’s regime would be toppled within “a matter of weeks”; actually, the fighting in Syria persisted and intensified. Two approaches then developed in Israel: one approach preferred the continuation of Assad’s regime, positing that “a familiar enemy is better than a new, unfamiliar enemy”; another approach argued that Israel should take action to assist in toppling Assad’s regime, since it is the “long arm” of the Iranian regime, in order to curtail Iran’s influence.

Above all, Israel failed to identify the historic opportunities for redefining geopolitical strategic objectives that emerged as a result of the tectonic changes occurring around it. In the context of the Syrian arena, over the last seven years, Israel preferred to remain cloistered in its comfort zone, focusing on tactical-military aspects and defining tactical military achievements as strategic targets. When the events began unfolding, Israel’s leadership focused its attention on two security objectives facing the Israeli military echelon: one was how to deal with the huge chemical arsenal held by the Syrian army prior to the outbreak of the civil war, due to the concern that one of these days, these weapons might be transferred to radical extremists or might even be used by the Syrian regime itself against Israel. The other objective was to prevent the smuggling of advanced war materials from the Syrian military to Hezbollah forces deployed in Lebanon and/or war materials falling into the hands of fanatic Sunni rebels and also preventing the fighting in Syria from spilling over into Israeli territory. Later, a third objective was added: preventing Iran from establishing in Syria.

No Israeli strategy

The Israeli political echelon had difficulties internalizing that political changes in the region were developing at an accelerated pace and on an historic scale.

Also within the context of providing humanitarian assistance, Israel took a very passive approach. True, Israel does provide some medical help to civilians wounded during the Syrian civil war who reach its border, and even allows the critically wounded to be hospitalized in Israeli hospitals, but it abstains from providing humanitarian assistance to those wounded who are not at its border and from launching substantive pre-emptive operations to prevent massacres of minority communities, such as the Christian and Yazidi communities who were slaughtered by jihadist organizations. The question about Israel’s involvement can be clarified when and if a substantive threat arises against the Druze communities in Syria living close to the Golan border. Such a scenario will force Israel to make a decision: to assist the Druze and prevent a massacre or to stand on the sidelines and watch the blood bath, while making do with assisting survivors of the slaughter who manage to make their way to the Israeli border.

Since the outbreak of the civil war in Syria, while the region has been undergoing an upheaval of epic proportions, Israel opted, as stated, to deliberately not show any active involvement in what was happening around it and to not take any side. Israel positioned itself as a kind of fortress that avoids any involvement in the events around it and repels anyone who approaches its walls – and decided to not become politically or militarily involved in Syria.

Israel’s passive policy enabled Iran and Turkey to promote their interests in the Syrian arena and, at the beginning of 2018, Israel found itself in an inferior position when an Iranian-Shi’ite spearhead appeared on its border in the Golan.

The Risk and The Chance

There is no doubt that any supportive action by Israel to this or that side is liable to affects its relationships with countries having interests in the region; it is also possible that Israel’s failed attempt to intervene in the internal battles in Lebanon in the 1980s is still haunting and is influencing its concerns about any similar intervention. Although excessive involvement and high exposure of Israel in the Syrian civil war is liable to trigger a direct confrontation with Iran or with terrorist groups in the arena, these factions and militias on their behalf are deployed, as stated, on Israel’s border, which shows that risks and threats that multiply in the face of a passive policy are liable to become strategic risks having far graver repercussions in the more distant future. Israel is liable to wake up one morning and face a geopolitical reality steeped in strategic risks that have been stewing over time as a result of an “everything will be okay” approach, a policy of pretending not to see the risks of the future, and preferring a controlled present, albeit replete with low-intensity confrontations.

Israel’s passive approach is also liable to drag it into a battle against its will, when it is ill prepared, in response to a series of rolling events or a single major event. This will also be the outcome of preferring short-term tactical measures over strategic operations having a long-range impact. It appears that Israel’s flexibility has diminished significantly ever since the Russians entered the region and began providing support to the Iranians in their de facto control over regions in Syria. Israel needs to develop sufficiently strong mechanisms of influence over what is occurring in the region – not only relating to routine security, but also relating to the future new geopolitical equilibrium in the region, if one materializes.

In recent years, Israel missed two significant opportunities to put its demand on the table for international recognition of its sovereignty over the Golan within the scope of changes in the regional arrangement in the Middle East. The first opportunity was in 2013, during U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry’s peace initiative for an arrangement with the Palestinians, when Israel could have demanded recognition of its sovereignty over the Golan within the framework of defining its long-range security needs on its eastern front and in the Jordan valley. The second opportunity was in 2015, against the backdrop of the signing of the JCPOA between Iran and the world powers, when Israel negotiated the components of its compensation for the security and strategic threats to Israel resulting from the JCPOA. As stated, it will be an historic failure today too if Israel makes do with accepting a tactical solution in the form of advanced war materials, instead of demanding constraints on Iran’s potential conventional acts of aggression and preventing the creation of a Teheran-Ein Gev land bridge by demanding that the international community finally puts an end to the aspiration of the Iranians and the Assad regime to regain control over the Israeli Golan, the area of which is less than 1% of the territory that once was Syria.

Israel, which, for nearly half a century, has been in dire need of global recognition of the necessity of changing its borders, finds itself at an opportune moment and in an optimal position to accomplish historic achievements. It should initiate a process of coordinating expectations again with the international community, led by the U.S. government – not only with regard to the alternatives for governing the territory between the outskirts of Quneitra and the Sea of Galilee, but also within the overall context of stabilizing the region. Israel must strive to achieve an international consensus, primarily by the Americans, that the time has come to nullify the “sanctity” of the 1967 borders and to internalize the need for demarcating new borders in the region according to the actual reality. The success of this course of action is contingent upon the ability of Israel’s leadership to recognize that this is a pivotal moment in history and that it must venture beyond its comfort zone and into an environment of uncertainty. It must try to influence what is occurring in the region and create a new political-security equation before we enter the last quarter of the first century of the State of Israel’s existence.

Israel is situated in the eye of the storm. Its involvement in the events in its environment has historic and strategic implications. In fact, Israel has not yet succeeded in comprehending the historic and strategic changes that are taking place around it, or its potential influence over them. Instead of a strategy of non-involvement and passivity, Israel should consider getting involved in a way that will guarantee its best interests in the Middle East under reorganization. As stated, the approach that posits that, by not getting involved in what is transpiring, Israel can remain a bystander and thus, presumably avoid confrontations, is actually an approach that is liable to weaken Israel – because prima facie, it has no influence on what is happening. Israel – as a regional power contending against other countries that are striving to gain regional hegemony, such as Iran and Turkey – will not be able to continue disregarding for much longer the monumental changes occurring at its doorstop. It must take initiative, and respond to what is happening, while being cognizant of the fact that this entails major challenges, but also major opportunities.